FOUR EXCERPTS

FOUR EXCERPTSThe lodge filled with Arapahos, perhaps a dozen women and a lesser number of men. They all wore baggy basketball shorts and carried towels. The women wore oversized T-shirts. The men were bare-chested. Stanford introduced me to them as they came in. I prayed for composure. They were polite and friendly, but I felt hideously self-conscious. I was the only non-native person there. I was nervous, toy-poodle nervous, a blonde curly-haired imposter at Stanford’s right side. Their glances prickled my skin.

Soon the rock pile was high enough that I was getting hot and the doors were still wide open. But there was no rushing. Everyone sat on the floor, smoking cigarettes and joking and gossiping. They seemed to have known each other all their lives. Then Stanford gave the word and the doors were closed, the flashlight extinguished, and I gratefully relinquished my foreignness, whiteness and discomfort to the encompassing dark. Stanford instructed a man to pour some water onto the hot rocks, and the heat bit into my face and arms and burned my lungs.

I pressed my nose and mouth to the ground moving along the base of the lodge where it met the ground, seeking coolness like a trout in a summer stream.

Stanford said a prayer, then invited people to share their concerns. The stories poured slowly into the shared blackness. One man said he had vengeance in his heart.

Sure, I thought chattily, join the club.

He continued. His son had been murdered by some white boys in the wintertime. They'd taken his shoes and clothes and dumped him in the middle of the high desert, leaving him to freeze to death. The investigation would go nowhere, he was sure of it. He wasn't going to do anything irrational, but still, he said, still he felt vengeance.

A wire of horror pushed into my heart, followed by a kind of hugeness. I felt glowing, luminescent, radioactive. A menace. My heart boomed in my ears. By the time I could listen again, a tribal official was speaking about the tribe losing land and how they'd have to unite to keep it.

Then Stanford led us in Arapaho songs and prayer. Then he made choking, convulsing sounds. The heat pressed against me like an iron. I took tiny breaths, the air hot metal in my throat and lungs. Then Stanford yelled, “Open it!” and the man sitting next to the door opened the door. The first of four rounds was over. It was down time, comfortable time, the time after the pain and prayer when you can get up and stand by the fire, or go inside and use the bathroom, or stay in the lodge and chat. Everyone lay there and told jokes. Everyone but me. I was so shocked and saddened about the boy left to freeze that I couldn’t even begin to chuckle at their relaxed humor. I was careful and quiet, hyper vigilant of my duties: putting Stanford’s cigarettes in his mouth, adjusting his towel. The second round passed. After that, the men brought in more hot rocks, just in case we were getting too comfortable. The third round came and went, and then the fourth. Near the end, I handed out the eagle wings I’d tucked into the willow structure above me to people who wanted to beat their skin and get even hotter. By the end, the singing was loud and joyful. Stanford said that the spirits take from him during the first three rounds, but give it all back to him in the fourth.

The sweat lodges were difficult, but I grew to love them, even when I emerged with a clanging headache that wouldn’t go away until the next afternoon. I felt cleaned out afterwards, body and spirit. Stanford sometimes said he wouldn’t be alive without them. Spiritually, I couldn’t even imagine the benefits he received. I could only hear him convulse and retch early in the sweat and dispense little jokes during the breaks (“Time to get going again,” he might say when it was time to start the second round. “Maria, hand me my goggles, and my cape.”) Towards the end, he sang with confidence and joy. I reasoned that getting so hot could only be helpful, physically, for a paralyzed person with circulation problems: the heart races, the blood sprints, banging at the walls of your system, looking for a way out. Bringing new blood to old wounds.

He didn’t consider himself a medicine man, but merely a spiritual healer, because his healing powers were available to him only in the sweat lodge. He’d often vomit as he funneled the bad medicine and sickness out of people, but none of it got on the ground because the spirits would take it.

Sometimes he’d be directed to a plant he’d never seen before, like one that grew by the river and resembled sage. As promised, it cured a man of cirrhosis.

After each lodge, Stanford met with the people who had come for help and told them what the spirits had told him the Creator wanted them to do. Over the years I would spend visiting, that advice included instructions for further ceremonies, or an explanation of where their lost child was, or a reassurance that their tumor was gone – “all that’s left is dried blood and scar tissue,” – or an admonishment that their cancer wouldn’t kill them but their chemotherapy would, or – this, time and time again – instructions to stop drinking or using meth, which was a growing problem on the reservation. He was middle management in the sweat lodge; he wasn’t the big boss. He didn’t heal people; the spirits and the Creator healed people through him.

“The Creator gives power to me and takes it away,” Stanford said.

He couldn’t prevent death. He explained that healers could delay it, or temporarily bring someone back from the other side, but he could not stop it. “When the Creator needs you,” he said, “he takes you.”

One of my favorite things about the sweat lodge was that it felt like a complete experience. During the rounds there was prayer, and urgency, and pain, and then the round would end and everyone would laugh and chat and lie there together, all of us sweaty in the dark, young and old, healthy and sick, Native and white. That’s one big difference between white life and the life I observed at Stanford’s: Here, adults have the feeling they are coming through the difficulties of life together. White people bear the difficulties of life alone, and then smile and wave like everything’s fine. The reservation is riddled with problems, but it felt a lot less lonely than the white world.

Daniel was Northern Arapaho Goth.

Once I said to him, “It must be really easy to do your laundry since everything’s black.”

He looked blank.

“When all the clothes are black, the colors don’t bleed onto each other,” I explained.

He looked at me quietly for a few seconds, then said with real feeling, “Yeah, but black FADES.”

One evening, Stanford was saying something to me like “when people are angry, they flare red,” and I was letting the statement work slowly through my white, unmystical synapses when Daniel yelled, “Aaaa!”

He was about four feet away from us, scrutinizing his face in the bathroom mirror.

“A hair!” he hollered. “On my chin!” Being from a northern and hairy race myself, I grew up believing that for 17-year-old boys finding a hair on their chin would be an occasion for joy, or perhaps relief. Not for Daniel.

He came over, thrust his chin into my face, and said, “Can you see it? Can you see it?”

I couldn’t, I promised.

“Oh man,” he said disgustedly. “I look like a man who lives on a island.”

What did that mean? Maybe he meant someone who’d survived a shipwreck. Or maybe for a Plains Indian whose life is all about roaming the Wyoming sage in his grandma’s borrowed Cutlass Sierra – which Daniel had done with satisfaction until a couple of months before, when he swerved to avoid a horse in the darkness and totaled the car, emerging characteristically unscathed himself – maybe for a young guy like that, living on an island would be a confining, bad, hairy experience.

I loved Daniel even though he bred pit bulls. He gave them delicate, feminine, frontiersy names – Daisy, Eve and Nell – but the dogs were still killers in the “I’m just playing but oops now I’m killing” way of their breed. They killed my favorite dog at Stan’s, a little mutt named Mark that ran with the pack around the house. Daniel was there when this happened, and had been bursting to tell me about it for months, but he had been sternly instructed to tell me the little dog had been killed by a porcupine. Mark was six months dead when I found out the truth, and I was grateful for the lie.

I loved Daniel even though he wrote violent rap lyrics. A lot of the boys at Stanford’s did this. His house sheltered a rotating cast of several boys. There were nephews and other relatives, plus kids the tribal justice and social service systems brought to Stanford to house and mentor.

What made Daniel unusual among his cousins and peers was that underneath the Goth clothes, underneath the part supermodel, part scarecrow presentation, underneath the rap lyrics, underneath all that, he was serious. More than serious; he was priestly. Other than his clothes and the pit bulls, he owned one thing: A DVD of the movie, “The Passion of the Christ” which he loaned out only with great hesitation.

Conversation:

Me: “Daniel, have you ever considered going for it as a Native American rapper, or using your looks to become a model and help your dad pay to get some decent fences around here?”

Daniel: “It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven.”

Stanford, from his bed: “Hey, it ain’t a bad thing to make some money, if it helps other people out.”

Silence.

Daniel, Daniel. Kicked out of Wyoming Indian High School in the ninth grade for fighting, he’d spent the last two years flopping around his grandma Stella’s house, which stood about 200 yards down the road from Stanford’s, borrowing cigarettes, using the phone to talk for hours to a girl who lived 12 hours south in Pueblo, Colorado. This presented a geographic challenge requiring the extraction of money and rides from not only his own grandmother, but his girlfriend’s as well.

He could charm his grandma out of $20 in about 20 seconds.

“She talks all tough – ‘I ain’t giving that kid another penny!’ ” Stanford told me, “and then he comes in and sweet talks her and she gives him 20 bucks! It’s embarrassing.”

Stella Addison was tough, but she’d borne nine children and now she was past 70. She was tired. Sometimes she had her grandkids and sundry relatives living in her house on a tight leash, badgering them to make pineapple upside down cake and Spanish rice for dinner. Other times there was a brawl.

I didn’t know what part Daniel played in the brawls at Stella’s, but I never saw him implicated. He was quiet, a Goth priest out in the yard playing with his dogs, moving below the radar of conflict and loss.

But then things started to change.

One night, a guy Daniel knew named Luke came in and started picking a fight. Luke cuffed Daniel, danced around, delivering some stronger, more serious punches to his face. Daniel leaned out and decked him in the nose.

Luke was taken aback.

“Why’d you do that, Daniel?” he asked, hurt.

“Cuz, man, you hit me first!” said Daniel.

It went from there, until Stella waded into the middle of the fight and broke it up, yelling, “I’m gonna call the cops on you kids!” and then did so.

“She called the cops on me,” Daniel told me later, his eyes lit up with triumph and affection and acceptance of the rightful order of things.

Stanford Addison was 15. He rode a green-broke horse beside the Little Wind River. Then he turned his horse away from the river and headed into the sagebrush. The horse tensed up, fussing and bucking slightly. Stanford wanted to put some miles on the horse to tire him out, gentle him down. Everyone in his family rode – his father Mervin, his mother Stella, and his eight siblings. His father broke all their horses. His older sister Arilda rode a horse to school in her miniskirt, tying the animal to a tree before she went inside. Another sister, Frenchie, and the younger kids sometimes snuck out on horseback before dawn to get away from all the housework. They’d eat corn and berries from the fields and knock each other off their ponies with long sticks, pretending they were the jousting medieval knights they’d seen in old movies.

Stanford and his brothers liked to drop from the rafters of abandoned buildings onto the backs of horses that had never been trained and see if they could stay on until the bucking stopped. He earned good money breaking horses the white ranchers and their sons couldn’t handle.

Riding through the sage, he was contented and calm. He was miles into the hills when something ahead startled him. There was a person on foot, an unexpected sight so far from civilization. But he or she – Stanford wasn’t sure which – beckoned him over, plain as day. He rode over the next rise, wondering if there was some kind of emergency, but when he got to where the person had been standing he found nothing but a spindly willow frame used in fasting ceremonies. There was nowhere for a person to hide – no gully, no trees, no buildings, just a shrubby slope. Stanford felt unsettled, as if he were being watched. The horse swiveled its ears around expectantly as if it did too. Stanford dismounted, left a cigarette at the structure as an offering and rode home. But he couldn’t shake that feeling of being observed.

This was his first brush with the world of spirits. They would appear to him again. More accurately, they would intrude upon him, because intruding was the only way they could enter the life of a teenager who was completely determined to ignore them. Stanford Addison’s mind was almost wholly focused on riding horses, having sex, drinking, dealing dope, driving fast and raising hell. When a high school teacher called him a “dumb Indian,” he wrestled the man to the ground and tried to strangle him. He broke into a café and robbed it. He shot white ranchers’ cattle just for fun. He reserved his most wanton behavior for women, whom he used, he said, “sexually, financially, the works.” As a teenager spending some time in Albuquerque, Stanford had seduced a Navajo girl – “a three-beer girl,” he’d called her, meaning it took three beers in his belly for her to start looking good. He had lured her away from a party and an aspiring young Navajo medicine man who loved her. Later, the Navajo boy came after Stanford. He ripped out a handful of Stanford’s hair and told him he would regret what he did. Stanford paid no attention to this. His favorite saying was “Eat shit and howl at the moon.”

So when he saw the apparition out there in the sage, he wasn’t really receptive to what it was or what it might be trying to show him. He would ignore the spirits for years. But they would wait.

After a few laps, she stopped in front of Stanford. He sat in the wheelchair he had occupied for 23 years, letting the mare’s skidding hooves throw up a small hurricane of dust onto his long black braid, his half-toned, half-atrophied arms, and slack legs. He squinted up through the fence. The mare tossed her head and whinnied, rolling her eyes piteously. I didn’t know much about horses, but it struck me as strange that she would make a point of stopping right there in front of Stanford. She tossed and whinnied in what started to look to me like an appeal. Stanford watched her until she was finished. Then he said in a low, gentle voice, “I can’t save you.”

This was a common occurrence at the corral – horses explaining things to Stanford. In the months and years that followed, he never discussed this phenomenon with me. He would finish up at the corral, roll his electric wheelchair into the house and turn on The Cooking Channel, now and then interrupting the program to ask me questions about pesto and sushi. Or we’d sit at his battered kitchen table sipping on mugs of Folger’s, and this paralyzed, six-toothed, one-lunged Plains Indian would take a drag of his Kool Filter King, sigh, and say something like, “I guess the thing I miss most since the accident is ski jumping.”

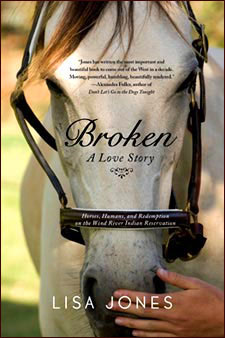

A joke. Stanford made me laugh a lot, which was a nice break from the confusion that often enveloped me during the four years I was a frequent visitor there. I wasn’t trying to write an authoritative book about Native Americans or native life. I was there to write a book about Stanford’s evolution from what he had been, a bad-boy outlaw, into the renowned medicine man he had become. But I didn’t get the information I needed in the quick question-and-answer sessions that had been the staple of my work as a journalist. I learned to wait and watch. And a lot of what I ended up watching was what was going on inside of me.

Only when I was nearly finished with this book did I realize what it was about – the journey I took following Stanford’s gentleness back to its source, a journey so different from anything I’d experienced before that there was no way to prepare for it.

Which brings me back to the mare, breathing hard and kicking up dirt and trying to make sense of where she had found herself. This is exactly what I did for much of the time I spent at Stanford’s. I too skidded to a halt and silently pleaded with him to save me, or at least to explain what was happening. But he couldn’t. Or wouldn’t.

The thing is, not only horses get broken around here. Everything does, starting with the ground itself. Millions of years ago, a new mountain range broke through the Ancestral Rocky Mountains, leaving the original mountains’ broken remains leaning against the flanks of the Wind River Range and the other mountain chains that comprise the modern-day Rockies. In 1878, at the end of the Indian Wars, the Northern Arapaho people arrived at the foot of jagged upthrust of the Wind River Range in their own state of brokenness, defeated, hungry, and ravaged by smallpox.

And then there was Stanford. His accident smashed his spine and left him on a slab in the morgue. He revived only to spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair. Along with his physical paralysis came some powerful healing gifts. At first, both his disability and these gifts seemed a terrible burden, but he haltingly came to understand that he had emerged from a small life into a big one. He had broken, broken through, broken out. His body was changed forever, but so was his heart. This happened in different ways to a lot of people around Stanford. I had no idea, that first time I visited him and watched his curious dialogue with the mare, that the same thing would happen to me.